A life of escapes, survival and rebuilding

A life of escapes, survival and rebuilding

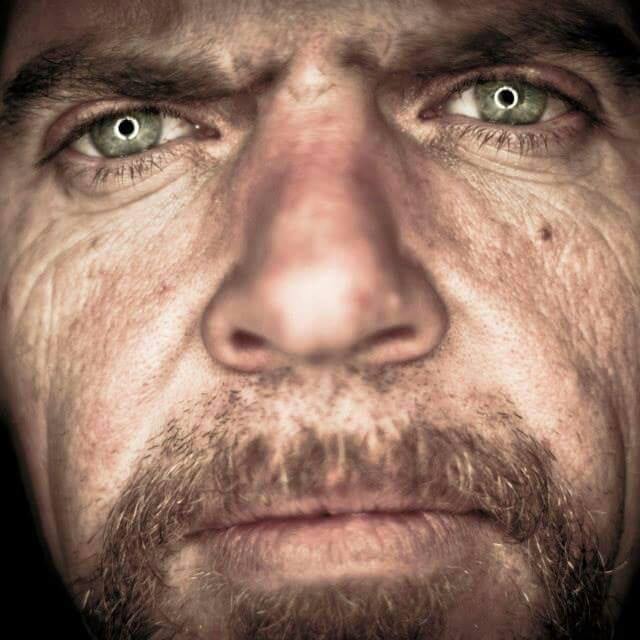

My life before the diagnosis: 35 years without knowing how to go home.

Childhood in pubs:

I spent a good part of my childhood sitting on bar stools, waiting for my parents to finish their alcoholic drinks. It was a world of smoke, loud voices, noise, and adults who weren't adults.

For any child, an unsuitable place.

For me, it was routine.

While other children played, I learned to wait.

To not disturb.

To adapt to whatever mood my parents were in when they left the bar.

I learned to gauge the atmosphere like someone learning to survive in unstable territory.

I couldn't explain it, but I understood that I wasn't safe. That kind of childhood leaves deep, silent scars that shape how you feel long before you can even name it.

The love that withdrew when I needed it most:

At home, affection was intermittent.

It could be there, but it could also disappear without warning.

There was affection, yes, but it was conditional on me not hurting anyone, not asking for anything, not needing anything.

When things went wrong, alcohol took its place.

I grew up learning that stability depended on the mood of the day.

That security was never guaranteed.

That if I showed vulnerability, there probably wouldn't be anyone there to hold me.

And that model stuck with me. It taught me to love half-heartedly, to protect myself from everyone, to run away when something became too real.

Not for lack of heart, but for fear that if I showed what was inside, I would be abandoned.

Adolescence and young adulthood: the long escape:

From 15 to 50, I lived trying to escape myself.

Alcohol and cannabis became my daily companions.

Then came periods of other substances, uncontrolled impulses, chaotic relationships, excesses wrapped in a feeling of emptiness I didn't know how to manage.

I traveled, changed countries, languages, jobs, people, beds…

but I was always the same.

It was constant movement without direction, an escape that only changed scenery.

I never managed to settle down.

I never let anyone truly see me.

I always disappeared before feeling exposed.

It was the only way I knew to avoid repeating the learned abandonment.

Suicide attempts: a shadow that haunted me since I was 14:

Suicide attempts were a part of my life from the age of 14.

They weren't a theatrical gesture or an attempt to get attention.

They were the desperate escape of a teenager who didn't know what was happening to him, who lived in a chaotic environment, and who lacked the tools to manage the pain.

For years, the idea of disappearing didn't sound dramatic.

It sounded logical.

As if I were superfluous.

That pattern accompanied me through different stages of my adult life. The mix of emotional emptiness, inner instability, and a lack of tools meant that, in the worst moments, my mind always offered me the same way out:

“You can stop feeling if you stop existing.”

When I received the diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder, I understood, for the first time, that it wasn't a moral failing, a weakness, or a dark whim.

It was a symptom.

A direct consequence of an unstable childhood, an overwhelmed emotional system, and years of nameless, accumulated pain.

From there, a profound process began:

talking about it in therapy, creating a safety plan, learning to ask for help, and starting to believe that my life was worth more than I felt it was.

Self-destruction and the lack of fear of dying:

For a long time, I lived with a strange feeling of not being afraid to die.

Sometimes it even seemed like a kind of absurd tranquility.

Over the years, I understood that this lack of fear was the direct consequence of having grown up in survival mode, without secure roots, without stable affection, without a firm emotional foundation.

It wasn't bravery.

It was exhaustion.

It was a form of escape.

It was the echo of a child who never felt protected.

The real issue: to live or to die:

Three and a half years ago, I reached a very clear limit.

It wasn't a scare.

It wasn't "I'll quit tomorrow."

It was a crossroads where only two options remained:

To live or to die.

I chose to live.

And that decision marked the true beginning of my recovery.

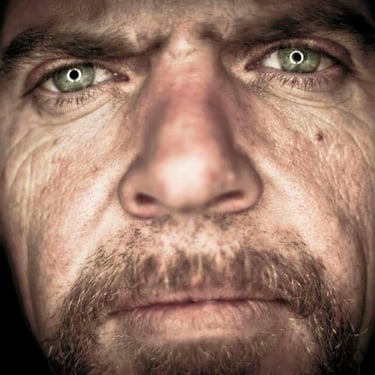

My son Lobo: breaking the story that had haunted me my whole life:

When Lobo arrived, my life took a silent but definitive turn.

He needed the exact opposite of what I received as a child:

a love that doesn't disappear,

a steady presence,

an adult who stays even on bad days,

someone who doesn't choose to run away, or drink, or create emotional distance.

For the first time, I understood that there was someone who only had me emotionally.

Someone who needed me to stay, even when I was broken myself.

Someone who couldn't pay for my wounds or my learned patterns.

I couldn't love him halfway, like I had loved so many people in my life.

I couldn't repeat history.

I couldn't disappear.

I couldn't run away.

And I didn't.

Lobo needed unconditional, present, and unwavering love.

And I decided to give it to him even before I knew how to give it to myself.

Important notice: The information on this website is for informational purposes only and does not replace medical, psychological, or psychiatric care. In case of emergency or emotional crisis, contact the appropriate health services. 📞 112 📧 ayuda@vivircontlp.com · Legal notice · Privacy policy · Cookie policy